The concepts of left and right in politics can certainly be contentious, with there often being little consensus especially as to what the left means among its self-proclaimed adherents. At times this leads people to abandon using the terminology altogether, and there are multiple versions of “post-leftism” among people who originally came out of some version of “the left”. For example, there is “post-left anarchism”, which can refer to a number of different tendencies, and in recent years in a more Marxist derived context there is a camp of people who have come to be called “the post-left”.

The most banal, conventional understanding would have us believe that “the left” is the same thing as “liberal” or “the Democratic Party”, but for anyone who has traveled through leftist ideology, and especially anyone who understands politics outside of the US, this is obviously not so. Social democracy, socialism and communism (in relative order of radicalness) are more explicitly what “the left” is than merely “liberal” or “Democrat”. And those groups sometimes conflict with each other, and even further, they have different interpretations and factions within them. There is also a distinction between the “cultural left” and the “economic left”, which also can at times have conflicts with each other, as well as foreign vs domestic policy positions.

Much the same could be said of “the right”, with the most conventional understanding simply being that “the right” is the same thing as “conservative” or “the Republican Party”. There is neoconservatism vs paleoconservatism, the economic right vs the cultural right, the religious right vs the secular right, and the libertarian right vs the authoritarian right. While it is often commented on that the right is a bit more orthodox in comparison to the left, it too has its own factions and internal conflicts. The rise of right-wing populism itself in recent years underscores an internal schism.

Thus, someone simply saying that they are “on the left” or “on the right”, while we can make some educated guesses as to what they mean, inherently requires unpacking and can mean all sorts of things. Are they a “social justice” type who also is pro-capitalist? Are they an anti-war conservative? Are they a Marxist-Leninist? Are they a white nationalist who supports gay rights? Are they a mutualist anarchist? Or an anarcho-communist? Are they a conservative Republican who supports some unions? Are they super into feminism? Which version of feminism? Are they a capitalist libertarian who was actually led to join the Democratic Party? Are they a social democrat who is anti-immigration and pro-nationalism? The devil is in the details.

The rub is that people are complicated and personal identity is irreducible. But while it’s true that the concept of the left and right has been problematized, I would argue that the most vacuous and problematic concept in politics is actually “the center”.

The Center Doesn’t Exist

Part of what can tempt people into identifying as a centrist is precisely this problem of irreducible personal identity, along with the understandable desire to not be pigeon-holed or be part of some sort of ideological cult where you must abide by an elaborate checklist of beliefs (two common examples of the latter being Ayn Rand’s Objectivism and Marxist-Leninism, which I think are remarkably similar in form even though they have radically opposing content). Therefore, “centrism” sometimes gets used as a stand-in for what really is “independent”. But by this definition, most people are “centrists”, including people who strongly identify and lean “left” or “right”.

What this conceals though is that there isn’t any specific position at all that this signifies, in a way that’s even more open-ended and less coherent than the “left” or “right”. Being an individual doesn’t make you a “centrist”. It makes you an individual, and it could be further said that the pretense of being an individual is itself loaded. While the desire to not be part of a cult is good, there is no such thing as a completely independent individual without biases. “We live in a society”. You are product of your environment and upbringing and implicitly have values. It usually is the case that people who make a point to identify as centrists actually lean liberal or conservative, and in some cases, they can even adopt positions that are “radical”.

This harkens to a serious problem with centrism, which is that talk of centrism often invokes the image of a completely neutral blank slate from with all other positions deviate. “The center”, along with “left” and “right”, is a spatial metaphor. But because everyone is, in fact, unavoidably affected by ideology, there is no consensus as to “where the center is”. One person’s center is another person’s left-wing or right-wing. As a human endeavor, there simply is no such thing as a completely neutral ground in politics to compare everything to. In this way, centrism often ends up coming off as a loaded rationalist posture, where someone claims to be post-ideological.

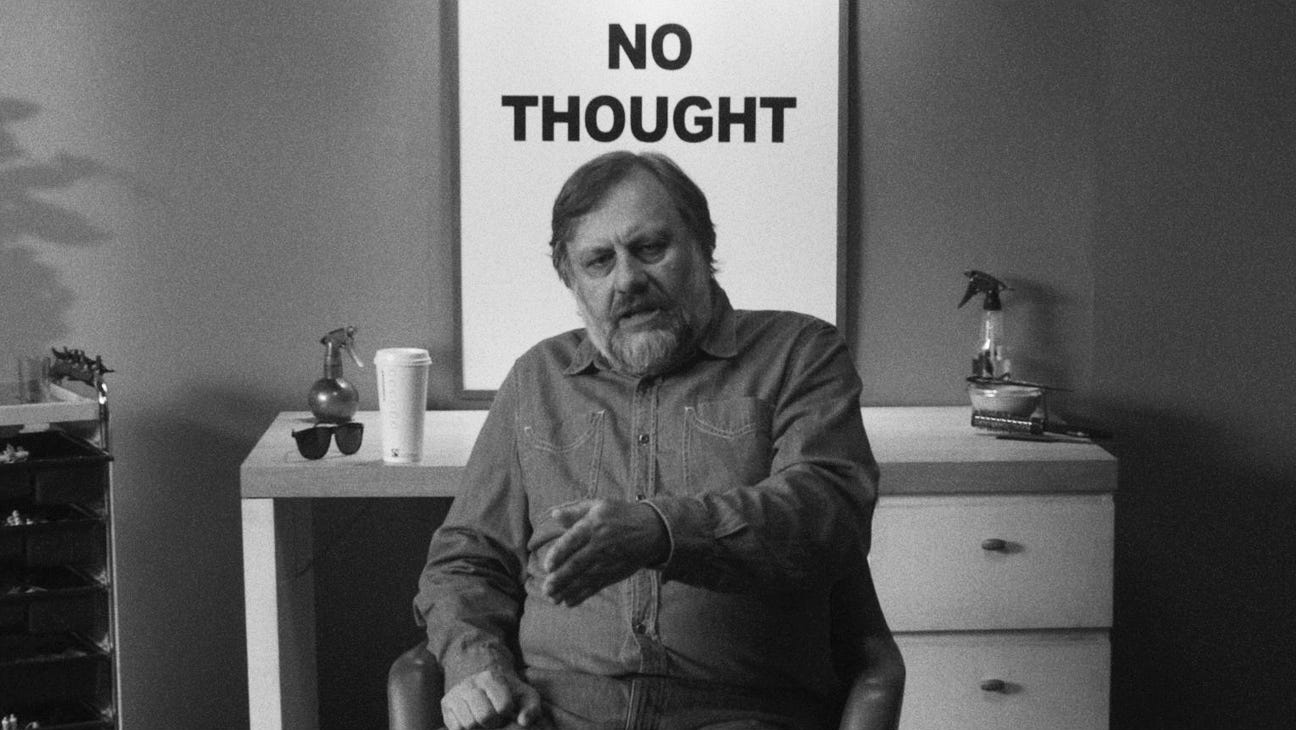

As Slovaj Zizek would seem to indicate, there is no post-ideological space.

People who position themselves as “enlightened centrists” are therefore quite justly resented by people all across the political spectrum. It is easily seen as a posture of rational superiority and faux independence. What’s more, due to the fact that politics often involves moral dilemmas and incompatibilities of fundamental values, the centrist is seen as a coward who refuses to take a position on contentious matters that require a clear answer or solution. The centrist makes a habit of equivocating “both sides” of political conflicts to a fault, and this becomes more and more difficult to justify the higher that the stakes of the conflict are raised. Choices must be made. But the centrist ends up being the naive person who says, “can’t we all just get along?”.

This itself actually reveals the centrist’s own implicit value-set as being focused on conflict avoidance. To be sure, there certainly can be contexts in which political conflicts are loaded or we can easily make criticisms of “both sides”, and there are definitely ways in which “the culture war” ends up looking like people are pitted against each other over things that are surface level, while there are more fundamental interests that they might actually have in common. However, it should be noted that the most sharp or keen versions of this criticism of the culture war usually implicitly entails that we do, in fact, accept a criticism of either capitalism or the political class, or both. Which itself entails or reproduces distinctions of conflict, of the working-class vs the capitalist or the regular citizen vs the state.

Thus, Marxist and leftist criticisms of the culture war invoke class conflict, while libertarian and conservative criticisms of the culture war invoke conflict with the state. Meanwhile, those who use the term “Cultural Marxism” critically have at times been known to argue against conflict-based politics in *both* economic and cultural terms; though it must be said that there’s a good chance that many of the people who throw around the term “Cultural Marxism” are themselves participants in the culture war and often are themselves quite blatantly right-wing ideologues of some sort, and the theory has too often effectively been a dog-whistle concealing antisemitic conspiracy theories. Which is itself rather divisive ideological garbage.

While there may be legitimate contexts in which both sides of a political conflict are wrong, it nonetheless remains a problem for the self-styled centrist that politics is inherently a sphere of conflict and that their posture can easily be criticized as being overly non-committal and cowardly, of not having any real principles when it matters. It is for this reason that centrists get duly mocked with memes depicting the centrist as a guy holding up a “compromise?” sign in a conflict between 50’s/60’s civil rights advocates and the KKK, for example, or between Nazis and Jews in the WWII era.

It must also be noted that because of the fact that the overton window or common assumptions of American political discourse is to simply assume that politics is a matter of “liberal vs conservative”, centrism is often framed as being something “in between” liberal and conservative. The problem with this is that it discounts political positions that fall outside conventional liberalism and conservatism, and people are prone to simply misunderstand and mislabel various radicals they may encounter. Thus, we get liberals who assume that people who are actually left-wing critics are right-wingers, or we get conservatives who attack right-wing libertarians as leftists. Furthermore, outside a US context, American liberals can be considered center-right. So what we consider to be left and right is also geopolitically relative.

Speaking of American libertarianism, the most conventional if not banal framing of it is itself a type of centrism. It is fairly common for run of the mill movement libertarians to claim that they are “neither left or right”, and the most standard “plumbline” libertarian position is to frame oneself as “socially liberal, fiscally conservative”. This could be seen as a type of centrism where one combines different aspects of liberalism and conservatism. We hear about the opposite framing, of people being “socially conservative, economically liberal” far less, though it is a thing. In either case, this would be a populist centrist understanding of things.

Of course, libertarians claiming to be “neither left or right” is problematized by the fact that its dominant ideological influence is, in fact, the economic right. The dominant narratives and educational institutions are all about economics, and common libertarian ideas could be seen as a type of economic reductionism. I remember well, back when I was myself a movement libertarian, how the propaganda model was significantly based on getting you to agree with capitalism, by framing it as a matter of liberty and the gospel of either Austrian or Chicago school economics. This is an example of how the pretense of centrism can conceal something right-wing.

Perhaps in conjunction with the tendency of centrism to represent a stance of conflict avoidance for its own sake or being non-committal, centrism can also take on the connotation of simply being “apolitical”. We probably have to unpack what it really means to be “apolitical” though. To a degree, it could be said that there is a large portion of society who are at least relatively apolitical, at least compared to people who involve themselves deeply with political culture on the internet, are invested in following current events on the news, as well as those who are active voters. Large sections of the population do not vote or do not follow what’s going on much.

Interestingly, liberals often harshly blame non-voters and “apathy” for the victories of their political enemies, while not reflecting on their own failures or perhaps the legitimate reasons why some people might actually be non-voters out of cynicism. In a sense, this could be seen as a form of “down-punching” or blaming the victim, as the non-voter is nonetheless just as affected by the decisions of political elites as everyone else. It’s a common refrain to hear “if you don’t vote you can’t complain”. I’ve actually always argued against this sentiment, as it presupposes that you consent even when you don’t even do so tacitly, and it’s a convenient way to silence independent dissent.

At the same time, it would seem that the self-styled “centrist” type of person, even if they do vote or follow political events, is “apolitical” in a sense. Or rather, they can be seen as engaging in “stealth politics”. One observable way in which the centrist can operate is to remain relatively silent about political matters in general, and then when they actually do suddenly talk about politics it is to give us epithets about conflict avoidance, to shame people for having strong opinions, or to talk about how they feel paralyzed about forming a judgement about anything. So, you have nothing to say, until you pop up just to tell everyone to shut up or be wise from your tower.

It certainly is true that too many people online give “hot takes” on events just as they happen without biding their time to uncover more information or formulate their opinion. But the “stealth centrist” could be said to swing too much in the opposite direction. They are disengaged to a fault or too scared to give an opinion. This can make people suspicious of where they stand, and when they do pop out of their hole to tell the rest of us how we’re silly ideologues, they come off as pretentious cowards.

What’s more, there is a type of “stealth centrist” who quite clearly is actually a conservative if not fairly hard right, but because they consider their views to be taboo, they are scared to publicly state them. There was a whole category of Trump’s supporters who fit this. There also is a whole category of self-proclaimed centrists who do somewhat actively engage in political dialogue, but their commentary reveals that their assumptions are clearly coming from a conservative bubble. There is also a category of the “post-left” Marxist sphere who fits this: people who have clearly abandoned the left or positioned themselves as contrarian to the left to a fault but won’t admit when they have obviously crossed the rubicon into being conservatives.

Even when the self-proclaimed centrist is not so much explicitly a politicized conservative, it could be argued that the centrist is often functionally conservative in the sense that their aversion to all radicalism precludes the possibility of any real change. If any and all politics outside of business as usual is automatically shot down as “going too far”, then what we get is more of the status quo. This leads us into consideration of “the center” as an actualized political force that is very much a real thing, if not the dominant power politics of the establishment.

The Ruling Class as the Authoritarian Center

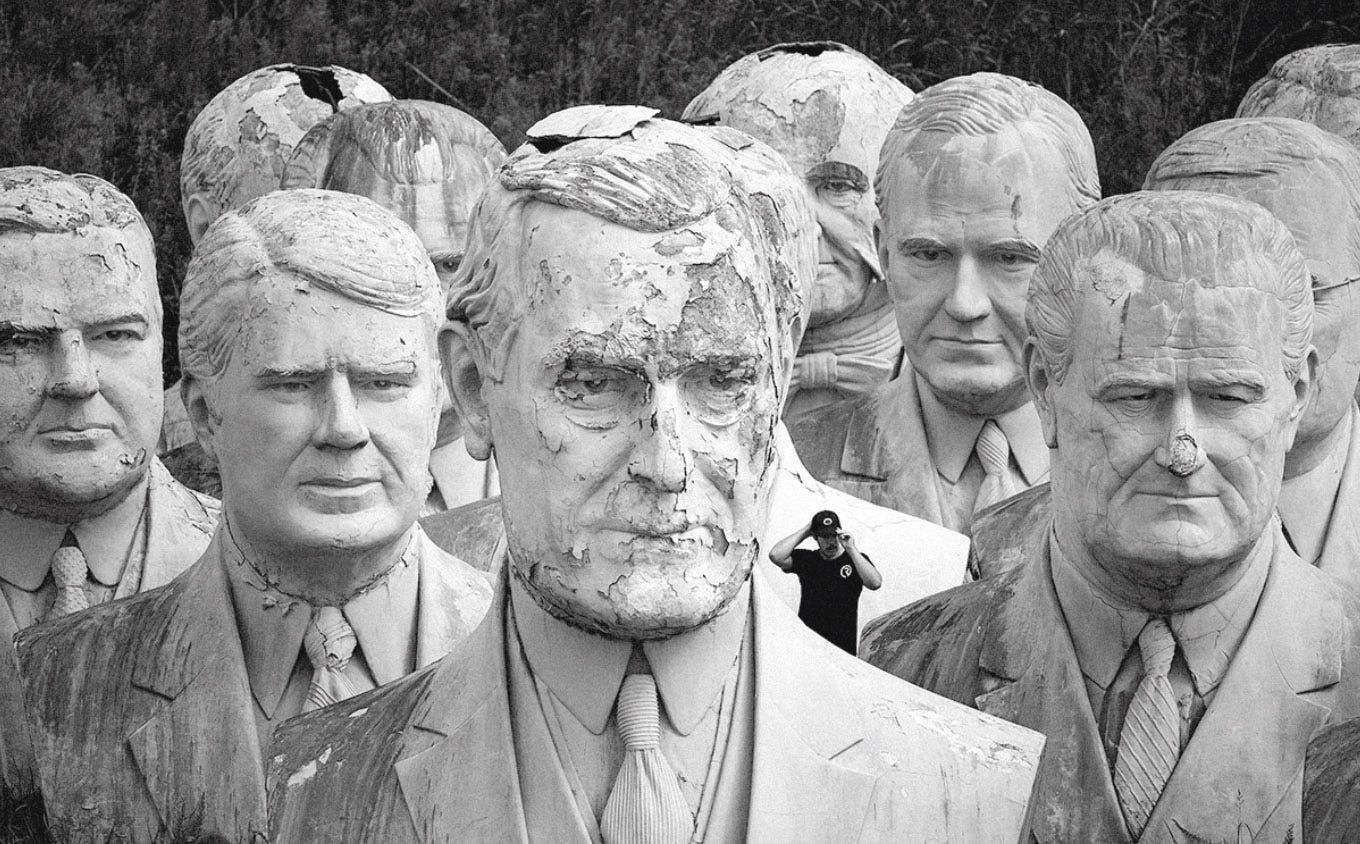

The attack of the ghouls…

In American politics it is a cliche at this point that, on one hand, liberals and the Democrats claim that conservatives and the Republicans are fascists, while on the other hand, conservatives and the Republicans claim that liberals and the Democrats are communists. A major part of the functioning rationale for voting for either the Democrats or Republicans rests not so much on any particular virtues on their part, but on the idea that “the other side” is an existential “threat to democracy / the republic”, on an authoritarian slippery slope into either communism or fascism or both (conservatives especially love to equate the two even though they definitely are different). People vote against rather than for, based on these fear-based narratives.

The paradox is that simultaneous to this polarization that seems to erode civil society, the political establishment and the state of American politics in its totality creates worsening economic conditions for the average person and alienates people, and it habitually kills off all serious reform efforts, causing an increase in distrust all around and giving rise to populist sentiment against the political and economic elite in general (which in turn is exploited by political elites for political capital). Revolution is certainly off the table, and transformative politics in general is halted before it truly starts or cyclically given the treatment of recuperation. Everyone is roped back into the center, no matter how radical their posture is. It’s the “eternal status quo”.

Furthermore, as multiple election cycles go by and the political process continues, both the Democrats and Republicans have effectively “traded hats” multiple times over, and this includes the Democrats increasingly adopting what used to be neoconservative and libertarian positions or even continuing some of Trump’s policies and rhetoric under different PR. “Bipartisan” legislation more often than not serves the core interests of the ruling class, as George Carlin once noted in a skit, and at the end of the day whether it’s Democrats or Republicans in power, we have been treated to continual wars, an ever-expanding executive, the regimentation of public opinion, hyper-commodification, and an intensifying generational wealth gap.

Benjamin Studebaker has commented on this paradoxical phenomenon of an alienated and disenfranchised generation of working people, fear-based rhetoric about all alternatives to the status quo being the end of democracy, combined with a status quo of so-called democracy that is static. One way to frame the establishment’s role in this picture is that the ruling class generally reflects what could be called “the authoritarian center”. While the partisan rhetoric frames “the other side” as communists and fascists, in some sense one could say that what we actually get is some strange combination of the worst of both; more specifically, a hyper-capitalist society with Stalinist characteristics. In some sectors of international politics, what we also get are strange political alliances and ideological co-mingling between neo-Stalinists and the nationalist far right. This may not be the dominant “center”, but it does represent a syncretic “3rd position” or “4th position” combining left and right.

One can also comment on this phenomenon in another way: we have a society in which both the market and the state have grown in power simultaneously. This contradicts the assumption that neo-liberal capitalism was some sort of “laissez-faire” thing, when it actually involves governments artificially creating and bolstering markets and coincided with a time period of increased state power. On the other hand, it also contradicts conventional social democratic assumptions, in which the growing power of the administrative and regulatory state is a bulwark against the rogue powers of the market, when the administrative state actually ends up collaborating with capital and standard regulatory practice is unable to stop the market from concentrating power. Instead, we get a nightmare scenario that both the libertarians and the communists feared: hyper-capitalism and hyper-statism at once.

This situation has also created confused narratives, especially on the right. We see conservatives concerned with massive inflation, corporate PR, and big tech, and the apparent move of capitalism into more of a rentier economy where people are less likely to actually own things, while calling it communism and floating the conspiracy theory that it’s part of a “great reset” plot by “the globalists” to force everyone to accept having less and de-growth. It is not all that uncommon to see conservatives giving sentiments that on the surface appear to very much be in line with anti-capitalism, in which the grievances of the disenfranchised worker is bemoaned, but without them actually connecting the dots between that and capitalism.

Meanwhile, the Republican Party has disingenuously tried to reframe itself as the working-class party despite the fact that it continues to favor policies that represent business interests, is rampant with politicians with connections to wealth and Silicon Valley, and escalates the very conditions in question. They simply present protectionism and the suppression of immigrations as the false solution, while they engage in “cancel culture”, media-suppression campaigns, and corporate/celebrity branding escapades themselves. Not very coherent. And, of course, Republicans continue the old pseudo-libertarian Reaganite rhetoric about being against “big government”, while they grow the government’s budget, buttress the police and military, and favor socially authoritarian law and intervention in the name of Christian Nationalism and traditionalist morality. Any free market or anti-state libertarian worth their salt should know better, but we live in a strange world.

The ostensible left is haunted by other types of confusion. We see left-liberals and the libertarian left being led into a stance of support for the corporate sector based on identity politics or so-called “wokeness”, defense of big tech and censorious information control based on concerns about misinformation and conspiracy theory (even though it’s used against them too), support for the national security apparatus as long as it’s supposed to be going after one’s political enemies, the adoption of neoconservative foreign policy stances and supporting funding for proxy wars in the name of opposing tankies (both real and imagined), and an embrace of a so-called “cancel culture” that is similar to China’s social credit system. A handful of years ago, quite a few liberals were even openly pining for George Bush Jr. and sharing articles portraying him as a sad man who makes paintings of the people he killed. Weird.

The Democratic Party, for its own part, has fully integrated neoconservatism into its platform and accepted the neoconservatives who fled the Republican Party into its fold, co-opted BLM and anti-police sentiment on the behalf of the corporate sector while actually increasing funding for the police and reducing anti-racism to symbolic moral posturing and token inclusion, and continued Trump’s immigration policies in many ways while positioning themselves rhetorically as securing the border and tough on crime. What’s more, under Biden, the Democratic Party has presented the posture that the economy is doing just great based on GDP and stock market numbers, and falsely claiming that they’ve undone the trajectory or effects of Reagenism, while the working poor and a lot of young people still continue to struggle economically.

No doubt, the political establishment do have conflicts between each other and the Democrats and Republicans are not identical. They take opposing stances on cultural matters, favor different regional blocks, and align themselves with different sectors of business interests, while the demographics of their supporters vary somewhat. Democrats still dominate the black and female vote (though less so than they used to), represent more coastal areas and the northeast, and are attractive to the underclass in some regards, while simultaneously representing white collar professionals and academics, along with having a good share of corporate sponsorship. Republicans in contrast are still more dominantly white (though less so than they used to be), caters to Christian religiosity, are more representative of rural areas and agriculture, have picked up a share of blue-collar types, have a lot of small business owners on their side, and still have plenty of big business interests behind them.

In this picture, the big business interests always have the most real power, however. The state is effectively “captured by capital” in these terms, in a way that inherently transcends party politics. The “military-industrial complex” also has its own interests that get channeled into policy in a fairly bipartisan way at the end of the day. Overall state power and the budget has endlessly grown across all administrations for decades. And while the Democrats and Republicans certainly can have their policy differences, it is hard for a critical observer not to notice how often they betray their own pretenses even when they position themselves as going against the grain.

Even Trump, who originally ran under the pretense of being a non-interventionist “America First” guy, caters to Israel anyway, while Biden, while he attempted to frame himself as the 2nd coming of FDR, was unwilling to go through with so much as a national minimum wage increase for anyone but government workers and promised that “nothing will fundamentally change” to begin with. Bernie Sanders, AOC and “The Squad” all endorse the centrist Democrats anyways, while governing like normal career politicians. All the core things that both leftists and libertarians have been criticizing the U.S. government about for years have been perpetuated. Populist demagogues rail against much the same things but capitulate to the system anyway. You can’t blame the public for being cynical in such an environment.

The “authoritarian center” considers you an unhinged radical who is a “threat to democracy” if you take up inconvenient criticisms, and even has gotten to a point where they memory hole parts of the internet they don’t like and algorithmically suppress people who agitate outside the overton window on social media. Meanwhile, a Democrat governor in California has the police invade and demolish homeless encampments, while the city of L.A. becomes unaffordable for anyone who isn’t rich. A Republican governor from Ohio considered to be a “moderate” accepts dark money bribes. Clearly, financial interests are still the “center” of power.

With all of this being said, calls for not rocking the boat and disingenuous rhetoric about protecting democracy ring pretty hollow, when the boat is sinking and there is no substantive democracy to be found. How can you protect democracy when 3rd parties are institutionally blocked from meaningfully participating in national elections, campaigns are run on corporate backing, and the two main parties don’t even pretend to hold internal primary debates anymore? And why shouldn’t people rock the boat when they are forced to put up with “more of the same” for generations that has led to institutional crisis? When you’re telling people from your own political alignment to not tell the truth because it would spoil the vibe of “hope” and “joy”, you’ve reached peak brain rot. Cold hard facts beat comforting illusions.

It’s time to start thinking long and hard about real alternatives, lest we perpetuate our own doom. We’re going against the clock. It’s ticking.